The economic environment in which multilateral climate policy operates to address financing the net zero transition in developing countries has severely deteriorated in recent years. The sharp rise in U.S. interest rates since 2022 and the likelihood that they will remain high due to fiscal and monetary uncertainties in the U.S. has negatively altered the global investment landscape, at a time when climate activism in the private financial sector appears to be retreating, especially in the United States.

These developments have already slowed the pace of green investments worldwide. Yet the urgency of reducing emissions in the developing world continues to grow. These countries are home to the bulk of the world’s population and, excluding China, account today for about one-third of global emissions and most of their projected growth.

The only viable solution is clear. It has been widely demonstrated that financing the investments required for the transition in developing countries – barring a highly unlikely surge in domestic savings and multilateral funding – demands a substantial increase in private external financial flows. (See: IHLEG Report).

The golden years following the Paris Agreement – marked by relative global stability interrupted only briefly by the onset of the pandemic, low interest rates, and market-driven green electrification – fuelled great optimism about the possibility of mobilizing private international finance at the necessary scale. This optimistic view was strongly endorsed in the lead-up to COP26 by the Gfanz-led coalitions of financial institutions and echoed by various multilateral agencies and governments.

Blended finance mechanisms, guarantees, and other risk mitigation tools were proposed to overcome the historic obstacle that limits North-South financial flows: the high cost of long-term private capital due to risk ratings and currency volatility in developing countries. However, despite apparent consensus, no concrete multilateral or private solution has been presented to significantly lower these risk premiums.

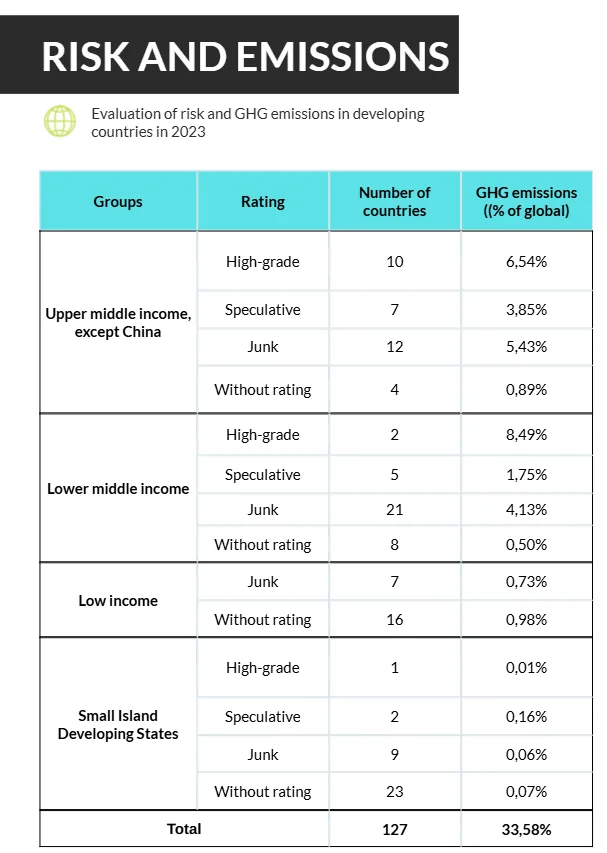

Brazil, with support from the IDB, launched a standalone initiative: the Eco Invest program, designed to attract foreign financing to support its Ecological Transformation Plan. The program’s first blended finance auction, held a few months ago, leveraged nearly six times the capital mobilized by banks to fund impact projects. Brazil’s success could be replicated in other countries, but it cannot be generalized as a universal solution. The group of 127 developing country signatories to the Paris Agreement for which emissions data are available is extremely diverse in terms of size, income, and especially sovereign risk ratings, as shown in the table below.

Thus, relying exclusively on private capital flows to finance the transition in developing countries should not, prima facie, be considered a universal solution. In fact, in countries with ratings near or above investment grade, blended finance structures – such as Brazil’s Eco Invest – can be effective and make a significant contribution to reducing total emissions. The 27 countries rated as speculative or investment grade-including major upper-middle-income nations like Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, and Colombia, and large lower-middle-income ones like India, Vietnam, and the Philippines-account for no less than two-thirds of total emissions from the developing world.

Nonetheless, this solution falls far short of meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals, as most developing countries are rated “junk” or are unrated by credit agencies. Fifty-five of them are low-income or small island developing states, effectively excluded from private capital markets. Therefore, even though market-based risk mitigation mechanisms are relevant and technically feasible to boost private financing flows for a handful of large EMDEs with reasonable ratings, an exclusive focus on cheap private finance in marginal volumes is clearly inadequate for the majority of developing countries.

Additional mechanisms are needed to fund transition projects in countries that are too poor and/or too small to attract the interest of most international capital market investors. A proposal to overcome this barrier in private risk perception would involve the creation of special funds to finance high-impact short-term projects in energy transition, nature conservation, climate adaptation and resilience, loss and damage, and just transition in the poorest countries.

These would require substantial public risk-sharing to attract complementary private capital. A positive point is that, according to current estimates, investment needs in developing countries are heavily concentrated in energy transition and nature conservation projects, which together account for no less than 75% of the total.

These categories are more likely to attract international private capital compared to the others, which resemble public goods. A recent high-quality study (see: Debt, Nature and Climate Resilience) offers a tested solution: the use of Financial Intermediation Funds (FIFs) such as the successful International Financing Facility for Immunization (IFFIm), or the Tropical Forests Forever Fund (TFFF), presented by Brazil at the 2024 G20 meeting in Rio de Janeiro and now progressing toward implementation.

In general, such funds are multilateral institutions governed with high standards, which issue bonds backed by voluntary commitments from developed economies and other investors, including subordinated-risk tranches. These funds build the confidence needed to mobilize private capital from markets at low cost and long maturities, enabling support for high-impact projects across various categories in low-income, high-risk countries.

A Proposal

A comprehensive solution to the climate finance challenge in developing countries would thus consist of two complementary funding streams:

• One stream would aim to unlock large-scale private international capital flows which have yet to materialize-highlighting the crucial role of blended finance instruments, credit guarantees, and creative hedging structures, such as those successfully implemented under Brazil’s ECOInvest program.

• The other stream would focus on designing a robust suite of FIFs targeted at specific types of impact projects, primarily for countries that currently lack access to private markets-that is, the vast majority of developing countries that signed the Paris Agreement-tailored to their specific needs.

These funds should be voluntarily capitalized by developed-country governments, multilateral institutions, and large philanthropic funds, and possibly supplemented by revenues from international carbon taxation mechanisms.

Naturally, access to the benefits of these funds should be subject to public policy requirements. These below-market-cost resources should be complemented by revenues from carbon credits tied to specific projects and by accelerating implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, as mandated in Baku, to increase unleveraged returns on impact investments.

The need to strengthen multilateral institutions

However, it is important to underscore that even reliance on public funding from developed countries for the transition may be impacted by the deterioration of the global macroeconomic and geopolitical environment. New fiscal austerity policies and shifting budget priorities, particularly under U.S. pressure in Europe, could restrict this type of spending.

This scenario underscores the need to strengthen the mandates of multilateral financial institutions in the short term to lead the design and provide financial backing for the creative public-private financing structures outlined above.

These institutions should also work to build coalitions of developed countries still committed to fighting global warming. To that end, it will be important to challenge the anti-climate-finance positions recently articulated by the new U.S. administration at multilateral forums, with a broad coalition of countries including other G7 members and China-still firmly aligned with the climate agenda. Brazil, as President of COP30 and a country committed to the climate cause, should play a leading role in this effort.